Dolphins have large, complex brains that are a lot like the human model — what if we could get inside their heads and communicate with them? Meet cognitive psychologist and marine mammal scientist Diana Reiss, PhD, who has been doing just that. Turns out our underwater friends have a lot going on in their brains, if only we could learn to decode it. Plus… Hear from one of the musician/scientists who discovered fifty years ago that whales produce actual songs.

Phil Stieg: Hello. Some of us remember the TV show Flipper and how he developed an appreciation for the intelligence of mammalian aquatic friends dolphins. Today we are joined by Dr. Diana Reiss, professor of cognitive psychology and marine mammal science at Hunter College. She has also been the director of the Marine Mammal Research Program at the New York Aquarium. Amazingly, she has spent 30 years studying cognition, communication and the evolution of intelligence in our aquatic friends. Today we’re going to learn how animals communicate and how we can communicate with them. Diana, welcome and thank you for being with us today.

Diana Reiss: Oh, it’s my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Phil Stieg: Let’s start with the basics – is communication important to dolphins?

Diana Reiss: I think so. I think we could infer that dolphins are mammals like we are. We know that animals communicate. It’s widespread in the in the animal world. They need it to be able to forage, to hunt, to keep in contact with each other. Communication is a necessary ability. I’ve been really interested in not only studying the nature of dolphin intelligence, but how might we communicate with this other large brain mammal that’s so different than we are in so many ways. How do we approach that kind of communication? So I study both how they communicate and how we might communicate with them.

Phil Stieg: Why not apes? Why not birds? Why not whales? Why dolphins?

Diana Reiss: The reason I got interested in Dolphins was that I was reading an article in The New York Times about whaling. And I thought to myself, this is really remarkable that we’re slaughtering these animals. We don’t know anything about them. This really propelled me into trying to figure out more about whales and dolphins. And that started the whole interest.

Phil Stieg: So the human brain is about 1500 grams or three pounds. How big is the dolphin brain?

Diana Reiss: Yeah, well, the dolphin brain is larger than the human brain. So if the human brain is somewhere between thirteen hundred and fifteen hundred, dolphin brains are way in closer to sixteen or seventeen hundred.

Phil Stieg: Does their brain look like ours is that does have the same folds, the same lobes and all that.?

Diana Reiss: Absolutely. It’s highly encephalized, it’s, it’s highly convoluted.

Phil Stieg: Encephalized means what?

Diana Reiss: It’s just a big complex brain.

Phil Stieg: OK

Diana Reiss: A really big complex brain. In fact the dolphin brain is the second largest brain when we look at brain mass to body mass comparisons. Our brains are the largest brain relative to our body size. Dolphins have the second largest brain relative to their body size next to humans.

Phil Stieg: Is there significance to that relationship between body mass and brain mass?

Diana Reiss: One issue is “what’s going on with all of that extra brain? What are they doing with it?” And that’s sort of what I do. I’m not really I don’t really study the brain of dolphins. Many of my colleagues do. I’m interested in what are they doing with these brains? And that gets into behavior that we can observe.

Phil Stieg: So how do we humans communicate with dolphins? I mean, the question is, how can you encapsulate your 30 years of experience and tell us briefly how you learned how to communicate with dolphins?

Diana Reiss: Well, I don’t know that I know how to communicate with dolphins. I’m trying to understand what kinds of information we can convey and what happens when we start having these close encounters with these Cetacean Minds. (Cetaceans, by the way, is the term for whales and dolphins.) And I would love to relate one quick story about what I consider my first encounter with a dolphin mind.

I was a doctoral student at the time and I was lucky to have a grant from the French government. I was able to go to a laboratory for biological acoustics in France. And I was had the ability to work with this young dolphin named Circe. I was asked to teach her to stay stationed, which means she would stay still when I brought her bucket of fish up and stay stationed in front of me and eat fish. And then I would give her the end signal and then she could do whatever she wanted. And I had to feed her these large Spanish mackerel. Their length was about three times the size of the width of her head. And I thought, this is not good. Let me cut it them up into three sections, heads, middles and tails. And once I did that, Circe readily ate the heads. She ate all the middles and she spit out. Every tail I fed her.

And I looked at the fish and I realized, well, maybe I’ll cut off the fins, maybe they were bothering her. And as soon as I cut the fins off, she ate the tails. So in a way, I joke that she had trained me to cut her fish properly, OK. Anyway, everything was going fine, but if she swam away from me prematurely, I would give her what’s called a timeout, which means I would back away and break the social contact between us, and she’d have to wait to get more fish, and that was going to serve as an error correcting mechanism. So these were brief. They lasted about 10 to 15 seconds and it corrected her. She learned, stay in front of me until I give her the signal that we’re done.

So several things happened that were quite fascinating for me. First, she learned very quickly to stay stationed. And when she waited till I gave her the terminate signal, you know, meaning everything was over and then we could just interact and I could give her a belly rub and I could play with her and I could give her toys. But as I was feeding her one day, I accidentally gave her an uncut tail and she looked up at me. Her eyes got rather large, and she made a beeline across the pool and took a vertical position and just stared at me. And I thought, “is this really possible that she’s giving me a time out? Is this really possible?” And then eventually she came back and as I gave her properly cut fish, she ate them all.

Now, this is an anecdote. What do you do with this? You know, and I didn’t want to be over interpreting this, but I thought I can turn this into an experiment. And what I did is I purposely continue to cut her fish perfectly over the next several days, giving her perfectly cut tails. And then I purposely gave her uncut tails on three different occasions over the next couple of weeks. And each time I gave her an uncut tail, she did that same behavior. Now to me, that was telling me She was using a mechanism that I use – the communication signal – back. And I think that was where I realized this is a mind to really contend with. We were going to have a lot of fun and it was going to be fascinating to study the species.

Phil Stieg: Aside from the interest of learning how to communicate with dolphins, did you learn anything about human-to-human communication? Have you been able to take anything from human dolphin communication and apply to human-human and improve our abilities to communicate, which is something I think we need in politics today?

Diana Reiss: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. Well, I think I totally agree. I think that my background was also in human communication and bioacoustics and symbolic behavior. And one of the things that I wrote up in my thesis was because I was looking at her abilities to communicate also doing visual tasks and how symbolic behavior begins. And I think what we understand now in terms of human communication is that we enter into this agreement of what’s going to be meaningful. It develops between us. And this happens with our children. We develop meaningful signals that we use. And others may not understand it unless they’re in those transactions with us, meaning it grows out of transactions. And there’s no absolute meaning in a message. It’s not in the message, it’s in us and how we interpret it and perceive it.

Phil Stieg: So that leads to my next question is what is the ecological or evolutionary significance of the communications that you have with dolphins?

Diana Reiss: A gain, I’m a reporter in my in a sense, where I’m engaging in controlled scientific experiments where I look how dolphins in general are perceiving. How what happens if you put a mirror in front of a dolphin, what will they how will they react? What happens if we give dolphins a means of communication? We’ve used interactive keyboards and now we’re using a touch screen, a giant touch screen with a dolphin. What will a big brain like this be able to tell us about themselves? And hopefully this will help us appreciate this kind of intelligence and appreciate these other animals in their environment and protect their environments.

Phil Stieg: You talked in your in your writings about the “dolphin Rosetta Stone”. What exactly does that mean? Was it a decoding of the dolphin language?

Diana Reiss: Oh, if only I could say we decoded it. No, we haven’t decoded it. We’re not even close to decoding it. What we’re trying to do is find approaches that will help us get insights into how they communicate.

I did an early study giving Dolphins choice and control using an underwater keyboard, where they had visual symbols on basically a keyboard underwater. And if they hit a visual symbol, they would hear a computer-generated whistle that was different than their own whistles but within the frequency that they’re using. So if one of the dolphins like Delphi, who we were working with, hit the triangle, he would hear a computer-generated whistle that sounded like this. And if he hit an H shaped symbol, that that would result. He would hear another signal that sounded like and we would give him a belly rub so they could ask for different things. And we looked at how that matched their preferences.

First, they started to imitate these sounds with great fidelity. And they started on their own to build associations, to develop associations between the sounds, the visual forms and the objects or activities they would get. So they showed self-organized learning. But beyond that, they started using them and bypassing the keyboard. So at one point I was changing the symbols on the board and one of the dolphins in front of me was whistling “rub” and rubbing on my hand and then put his basic contact call after that, which we think is sort of like an identifier for a dolphin. And we got that on several occasions that they started to actively use that. So we’re giving them an artificial code to see what they’re doing. And they started to use it and they started to use it on occasion between each other, it was wonderful.

Phil Stieg: We’ll return to our discussion with Dr. Diana Reiss after a short break. In the meantime, let’s hear about a discovery made 50 years ago that changed the world’s understanding of another intelligent marine mammal – the humpback whale.

Interstitial

Narrator: It was a sound that had been both familiar and mysterious to mariners since ancient times. We now know that these haunting echoes are the voices of whales.

In the late 1960’s biologists Roger and Katy Payne went to Bermuda to study these vocalizations. Katy had studied music at Cornell University, and Roger, who had previously studied echo location in bats, was also an accomplished amateur musician. This background was crucial to their signature discovery…that these sounds were not just random vocalizations – they were “songs”. Complex, repeatable songs – shared by a community of whales, and taught by one generation to the next.

50 years later Katy describes that discovery:

Katy Payne Phone Interview: Roger and I were looking at spectrograms, and as I analyzed them, I saw right away that we had repeating cycles of sounds and in in the same kinds of patterns. So they were all singing songs and the songs all contain the same themes which contained the same kind of phrases.

There’s something very elegant going on. They become complex organisms, just as we are… I was just the one who listened and freaked out and figured out what was happening.

Narrator: With the release of their long-playing record “Songs of the Humpback Whale” Roger and Katy revolutionized the image of whales in popular culture. Whales had previously been fearsome leviathans – monsters of the deep. (That’s why Moby Dick had such a bad attitude…) But overnight, they came to be seen as gentle giants – intelligent, emotional creatures worthy of our respect.

The Paynes recognized the aesthetic power of these songs, and knew they had to share them with other “human musicians”. Which is why, in the summer of 1970, Roger ended up taking his tape player and headphones to stand outside the stage door of the Delacourt Theater in Central Park. One of his favorite singers was appearing there in a production of Peer Gynt. Like a self-described “stage door Johnny,” it was his hope to run into her after the show and possibly have a chance to play his discovery for her.

(Fade under Judy Collins “Farewell to Tarwathie”)

He did get that chance… And several months later, Judy Collins released one of her top selling albums – Whales and Nightingales – giving Roger and Katy’s musical marine mammals a special place in the hearts of music lovers everywhere.

(music fade out)

Phil Stieg: So do you think dolphins have an emotional life?

Diana Reiss: Oh, definitely. Dolphins and most animals are emotional creatures. And there have been many studies looking at the brains of other animals and our brains, and we have very similar structures in our brains, in the mammalian brain. And you can see emotional behavior. In fact, it’s interesting, that you asked this Phil, because for such a long time, we thought animals were generally just using emotive signals. Charles Darwin, he wrote a whole book about emotions in humans and other animals, and that was that was controversial at the time. It didn’t go over quite as well as his original book, Origins, You know, Origins of Species. But now it’s well accepted that animals do have a variety of emotions, whether it’s like what we do exactly, we can’t say. But they show anger. They show, you know, pleasure.

I think people who have animals in their homes as companion animals get it. You know, I think it’s pretty evident and they’re developing their own forms of communication with their pets and they see that the animals are acting emotionally as well.

Phil Stieg: Tell me what your “wow” moments were. And you probably have had too many, you know, we could spend an hour with that, but a couple of wow moments.

Diana Reiss: Thanks for asking. Yeah. One of the wow moments was obviously when I worked with the mirror asking the question, how would a dolphin react if he saw his face in a mirror? So, so far to date, humans show mirror self-recognition. As we know our own species. The great apes show it. Monkeys generally don’t unless there’s some really extenuating circumstances. Dolphin show at elephant show it. And again, large, complex brains relative to their body size. It takes time for dolphins to realize that, hey, that’s me in the mirror. And when you put a mirror in front of them, the actual behaviors they show are very similar to what we do and what great apes do in front of a mirror. They’re interested in looking at their eyes up closely. They examine the insides of their mouth. They even look at their genitals. They’re looking at parts of their body they cannot see in the absence of a mirror. And then they actually do a variety of unusual behaviors, much like we do. You know, you check out what do you look like when you do that dance step. So that was a “wow moment”.

Phil Stieg: So where are you going next? What’s on the horizon?

Diana Reiss: Well, we were supposed to be in Italy …

Phil Stieg: I want to come, sign me up!

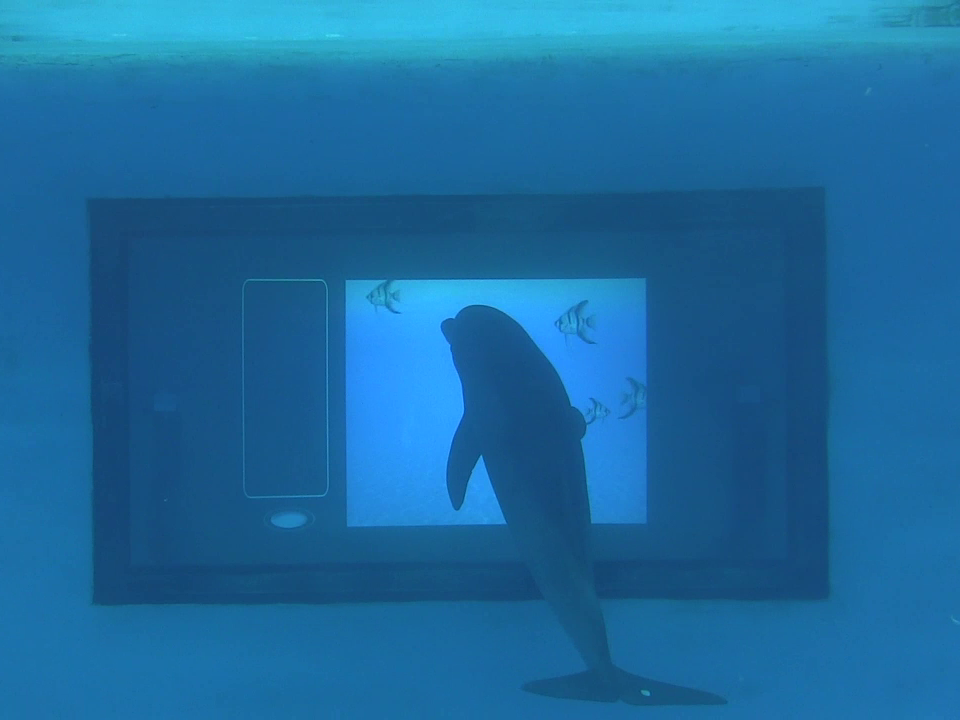

Diana Reiss: We were supposed to be in Italy doing our study with dolphins. And we spent some time at the National Aquarium piloting our large new four by eight-foot touch screen. We got some really interesting preliminary results. We already started seeing some vocal mimicry and interest by our dolphins.

I have to say that the very first time we introduced our dolphins to the touch screen are one of the young dolphins named Foster immediately came up and started interacting with it. Can you imagine this animal, non-handed, non-technological. He was interacting with a game w e made a specially designed dolphin game called “whack-a-fish” based on whack a mole where they were just fish moving across the screen and no sound involved. He hit practically every fish from the first moment he saw the screen turn on. And I think that we’re looking to see how can we give them stimuli and programs so that they how could we give them stimuli and programs that they could interact with? How can we learn about their mental capacities? How can we get reflections of their minds, a window, so to speak, into the minds of dolphins? We’re also hoping to do more field work when we can get back out there.

Phil Stieg: And you’re actually using drones now?

Diana Reiss: What we’re trying to do is find approaches that will help us get insights into how they communicate. So as you mentioned, we’re now using aerial drones in our at our field site in Belize, where we can hover above them invisibly. So we’re not interfering with what they’re doing and look at them through a lens that’s quite different. We can look down upon them and see the patterns of their interactions while we’re downstream, a half a mile in our boats recording their vocalizations. And that’s giving us great new insights into what’s going on. One of my doctoral students at Hunter right now is doing this for his thesis. And I collaborate with Marcelo Magnasco at Rockefeller University. It takes a village when you’re doing this. It’s not just me.

Phil Stieg: So you also talk about what’s fascinated me, this concept called the “Interspecies Internet” and is, you know what the mental lives and intelligence of animals is. Are you saying there’s a spectrum of communications and we as human beings need to work a little bit harder so we can understand the animal life around us? And the next question then is what is the importance of that?

Diana Reiss: Several years ago, I was approached by Peter Gabriel, the rock musician and visionary, because he got interested in some of the work I had been doing with dolphins. And we were then joined by Vint Cerf, who was the co-founder of the Internet, and Neil Gershenfeld, director of the MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms in the four of us have been working together. It may sound like an unlikely team…

Phil Stieg: Interesting cocktail party.

Diana Reiss: Right. And where we formed this interspecies Internet, we’re now calling it “interspecies I-O” – input output. It’s really to bring a forum together and stimulate research in the area of interspecies communication. How we can learn more about the minds of other animals by finding better ways to communicate with them, giving them systems of choice and control, much like what we’re doing with the touch screen, but also deciphering. And again, one of the main areas of our focus is this deciphering how do we decipher the codes of other animals.

Phil Stieg: For the skeptics out there that are listening to this, you know, they’re thinking, gosh, we got Covid, we got infectious disease, we have limited resources. Why is this kind of work that you’re doing? Why is it important?

Diana Reiss: You know, for a long time, we’ve seen ourselves as humans at the pinnacle of that evolutionary tree that we’ve gone you know, we’ve gone to its heights and that every everybody else is below us. And I think that so many multitudes of studies from the field and from controlled laboratory studies of behavior have shown that, no, we’re not alone in these abilities. If you look around us at the branches that are on similar levels to us in the same level, there’s this multitude. There are multitudes of species that are intelligent, that are sentient, that are living and have been evolved to fit their environment very well. Maybe that’s threatening for some, but for so many it’s feeling you feel this wonderful sense of company. We’re not alone with these other, you know, intelligences and let’s respect them.

Phil Stieg: Dr. Diana Reiss, thank you so much for being with us. You’ve taught me that there is a communication between us and, frankly, all animals and there’s an emotional component and there’s a companionship component to it. And I think that all people need to become more aware of the animals around them, the relationship that they bear with those animals and think more clearly about how we need to protect their lives and what they bring to our lives. Thank you so much for being with me.

Diana Reiss: Thanks so much for having me. It’s an absolute pleasure.