Delve into a comedian’s brain to discover what makes people laugh — and when the comic is also a neuroscientist, it’s no joke! Dr. Ori Amir studies what goes on in the brain as jokes are born, and he’s also learned how to “get out of his head” to write some pretty funny stuff. Be afraid: He is working on using artificial intelligence to come up with new puns to make us groan.

Phil Stieg: Welcome! Today I have with me Dr. Ori Amir, Dr. Amir is a neuroscientist at the University of California. He is a leading researcher on the way our brains create and understand humor. Probably equally important, he is a part-time stand-up comedian. He is here today to help us understand where humor originates in the brain. Ori, welcome.

Ori Amir: Hello!

Phil Stieg: Before we even get going or a can you explain to me what is a joke and what constitutes humor?

Ori Amir: Humor, I believe for something to be funny, it has to have a logical mechanism and in which there is some kind of a switch of perspective. So you have two scripts or two possible ways to interpret a situation and and you switch between one to another essentially. It doesn’t have to be the listener being surprised or switching. It could be somebody else that is being observed, you know, like in a practical joke, you know, what’s going to happen. But you still find it funny when somebody else is being surprised. And then there is the emotional mechanism by which the joke has to make you somehow happier. It could provide a relief, titillation, their schadenfreude, the switch of scripts somehow make the listener happier.

Phil Stieg: Is humor or a joke one of those things that a beauty is in the eye of the beholder. What you might find humorous, I don’t necessarily?

Ori Amir: For sure, although the you probably would recognize something as a joke even if you don’t find it funny. So there is a structure to it. There is a logical structure to it. If you at least understand the language and the reference, you would know it’s a joke.

Phil Stieg: Can you go to school? Can you go to a class and say, you know, all of a sudden I decide I think I have a sense of humor. I want to try to be a little bit funnier. Can you go take classes on how to construct the joke and be humorous?

Ori Amir: I’d say, yes. I mean, there definitely would be the people who would say, no, you’re born with it. And it’s a talent. And I think it’s a combination of both. And, you know, it could be helpful. It could help to an extent. I’ve seen people improving with comedy classes .

Phil Stieg: Yeah. So, do you personally – You get more satisfaction or equal satisfaction out of studying humor or being a standup comedian.

Ori Amir: It varies and I guess I guess an emotionally thrilling to a greater extent is is actually is performing comedy.

Phil Stieg: So, your research focuses on the brain’s function as it is involved in what creating humor is that the approach that you’re taking? You’re looking at process, function or the result in the brain?

Ori Amir: It’s a whole process. When you were exposed to a joke, for example, you know, there is that initial processing and then when you get the joke. And the same for comedy generation, I looked into what is the difference between, for example, professional comedians and amateurs and non-comedians that their brain activation during the process of coming up with a funny idea. So it’s a sequence. There’s a bunch of stages to it.

Phil Stieg: So, you’re, you’re fundamentally looking at a person’s process of writing a joke? Is what you’re looking at?

Ori Amir: Yes, sir.

Phil Stieg: Let’s break it down into a process, OK? So, what parts of the brain are activated when a comedian is creating a joke?

Ori Amir: The short answer is pretty much everything.

(music)

But there are areas where the unique things that have to do with writing jokes happen.

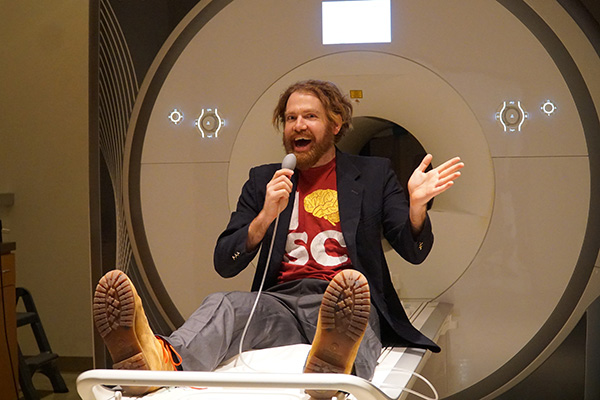

So in our experiment, what we did was we shove the those comedians and non-comedians into this tube, the MRI machine.

Voice Inside Comedian’s Head – “So this is an MRI Machine? Man! Who knew it was going to be so cramped … (noise starts) … cramped and really noisy! – This would be a bad time to learn I’m claustrophobic.

Ori Amir: And so basically they’re lying there, and they’re looking through some mirror were some New Yorker cartoons are being displayed. And they basically have to come up with captions in 15 seconds to those to those cartoons.

Voice Inside Comedian’s Head – Ok, so what have we got? A psychiatrist’s office – and there’s an elephant on the couch. Um… “Geez Doc, I wish I could forget sometimes”? No, no. How ‘bout “I’m in the room and NOBODY will acknowledge I’m here!” (rim shot sound effect) Yeah!

(music out)

Ori Amir: So, this is the task.

Phil Stieg: Now the assumption is that the caption is humorous. But in reality, how do you determine whether it is humorous?

Ori Amir: Well, first of all, I ask them to come up with a humorous caption. (laugh) Also we do have we do save those captions and we give them to some undergraduate students who have who have to do our experiments and they have to rank those captions for funniness. Each caption was rated by something like four undergraduate psychology students. And the average rating was the funniness of the joke.

Phil Stieg: Are your subjects willing? Is this a happy time for them to work with you?

Ori Amir: And it beats the alternative, some of the other experiments they could have done.

Phil Stieg: (laughs) You’re gonna start with painful electrical stimuli and see if they can crack a joke under those circumstances, huh?

Ori Amir: If you’re taking introduction to psychology, you participate in some experiments and ours. Our experiment was not one of the more boring ones.

Phil Stieg: So, did you see the parietal lobe light up ?

Ori Amir: Obviously you would see areas in the brain involved in vision like, you know, processing the image in areas involving in language in, you know, just just crafting the sentence that that makes up the caption. But we try to see what is unique to humor creation. And we think that there and certain areas in the temporal cortex like the area next to your ears, this is sort of a high level area where information from all over where the brain converges which allows you to essentially put together remote associations. Many jokes are about the surprise. I f you want to surprise somebody, it has to be a remote association, but it also has to be something that is not completely unrelated. For information from remote areas of the brain to to converge and to be become meaningful as a joke, and it has to be in an area where in terms of the architecture of the brain, this is possible. And this area next to the ears is where this kind of action is possible.

Phil Stieg: What difference did you see between trained comedians and, as you call it, amateurs, you know, did different parts of their brains light up?

Ori Amir: The same brain areas are activated, so it’s not completely different for them. But you have a difference in magnitude. So and the temporal area that we described has been activated more in amateurs compared to non-comedians, and more in professional comedians compared to amateurs. But at the same time, at the prefrontal cortex, the area in the front of the of the head, and that is involved in in control of the thought process. So essentially, it’s kind of like the conductor of the orchestra. The creative ideas don’t come from it, but it’s kind of directing the creative process. So it’s less activated the more experience you have. And you need less of a conductor to an orchestra when you when you have that professional musicians, essentially.

Phil Stieg: Or you’re less inhibited. I mean, since this is the executive function of the brain, probably, I would suspect, tamps down some of our zanier ideas.

Ori Amir Absolutely.

Phil Stieg And to be a comedian you don’t want to tamp it down. Right?

Ori Amir: And that is what I think one of the more common advice that, you know, improv teachers give students is “get out of your head” , meaning you want to disinhibit your thought process. And so I guess the translation to neuroscience language would be, you know, “Reduce the activity of your prefrontal cortex!”

Phil Stieg: Well, I would presume that that’s true in all of the creative forms of, you know, art, music, other things. You want to be more expansive. Correct?

Ori Amir: Yeah, I mean, in the end of the day, you do want to have some and some direction and some logic to the composition. You don’t want to be completely random. And this is why perhaps like the one common factor or the one common area that is activated in all kinds of creative processes like rap improvisation to jazz improvisation, to painting all seem to activate this pre-frontal cortex area. But the magnitude apparently is smaller for the more experienced.

Phil Stieg: Was there any major surprise as you were going through all this? You went, oh, my God, I didn’t expect that at all.

Ori Amir: One thing that we found was that… The striatum is a reward region, so essentially anything that you do that is rewarding, so you eat sugar, you look at a picture of a loved one, also when you enjoy comedy, you would see activation in this area and the striatum. So, what we found that that activity in the striatum before you even come up with the joke at the very beginning, predicted to some extent how funny the joke is going to be that you write.

(Music)

Phil Stieg: I’m sure there’s differences between being a neuroscientist and being a comedian. Are they both equally difficult?

Ori Amir: Funny enough, I feel like in neuroscience, you know, it ends up losing its challenge at some point, whereas comedy keeps being challenging. But that might be just because I haven’t worked on it enough. You can take your skill and intelligence to to its limits and with both with both pursuits.

Phil Stieg: So may I ask you to combine both and do you have any good neuroscience jokes?

Announcer: Ladies and Gentlemen, put your hands together for the comedy stylings of Dr. Ori Amir, PhD!

Ori Amir (on stage in a comedy club)

So, as you can tell by my accent, I am a neuroscientist.

Well, I just got my PhD. And if you’re all wondering what’s the difference between a Ph.D. and an M.D.? Em, it’s about 10 times less women.

When I told my friend that I am going to LA to pursue a Ph.D. at USC. They said, “Wow, you must love learning!” No, I just really like acronyms!

My dream is to become a professional comedian and an amateur neurosurgeon. If you all want to have a PhD like me, here’s what you gotta do. It’s going to take seven years. In the first five and a half years you’re going to work very hard on developing a silly accent.

And then you do some original research, and it all culminates in a dissertation defense in which you present your work in front of five important neuroscientists. And if you fail, they eat your brains.

Yes. Thank you very much ladies and gentlemen. (applause)

(Music under & fade)

Phil Stieg Which came first for you. Was it being a humorist – or was it being a neuroscientist and then you got interested in humor?

Ori Amir: Well, I was I was a neuroscientist first you know, I was studying it and the university I was at, USC in Los Angeles. They had a comedy group which I just accidentally ran into. And I was like, “Oh, that is fun”. You know, I tried it and I was I was hooked. And Los Angeles has a lot of open mics and a lot of comedy clubs. So I just got involved in the scene. And I was actually feeling guilty that I was like, oh, I’m wasting too much time on comedy or I’m wasting too much time on neuroscience, depending on what I was like thinking I’m going to be in the end at the time. But then I figured I can potentially combine those two, and especially since I was in Los Angeles. And, you know, we’re not far from half of the famous comedians in the world and we have a fancy brain imaging machine. I guess I was lucky. I was just in the right place for comedy, in the right place for brain imaging. And it just I didn’t even I didn’t plan any of this, but I realized the potential of the situation.

Phil Stieg: So is there something about nighttime and humor? Because, I mean, if you think about it, the nighttime shows – Johnny Carson, Jay Leno, of all the stuff, Saturday Night Live, all that’s at night. You never hear of a mid-afternoon comedy show.

Ori Amir: I don’t know what it is. I think something about darkness and you feel less inhibited to laugh. You want the room to be dark. You want the people to sit close together. You want the ceiling to be low. All of those those elements appear to make people laugh more.

Phil Stieg: I just don’t know whether at night, I’d have to look, as to whether, you know, more serotonin or dopamine is released when we’re getting ready for bed. So it puts you in a happier mood to appreciate a good joke.

Ori Amir: You know, that is very possible. I actually don’t know it myself. But it also the darkness itself plays plays a role. I’ve been performing in the evening in some countries where the sun goes down at 11 p.m. and it’s not it’s not a very easy place to perform.

Phil Stieg: Really? OK. That’s amazing.

Phil Stieg: Ori, when you’re performing, is there a high that occurs and how long does it last?

Ori Amir: Em – not as often or as long as I want it, but — being nervous. I rarely am nervous recently before performances, but if I am, it’s usually results in a better performance and a better high.

Phil Stieg: So question to you is, what about, you know, taking this into the therapeutic realm? What about humor, therapy? You know, in this day and age with Covid, how can we just get people to lighten up a little bit and stop worrying so much?

Ori Amir: I feel I feel like our major aim of the field is the field is to make people people keep worrying.

Phil Stieg: You want to keep people worrying?

Ori Amir: It seems like if you watch any of like those comedy shows, like The Daily Show or whatever – it’s all about getting people to stay worried.

Phil Stieg: Yeah. (laugh)

Ori Amir: You can you can consider comedy clubs for comedians to be humor therapy.

Phil Stieg: The comedians themselves.

(Music)

Phil Stieg: So the take home message from from all of your research is — question mark?

Ori Amir: We’re still working on the question.

Phil Stieg: And yeah, you never have the perfect question. Right?

Ori Amir: I mean, if we had the take home message, we could have retired.

Phil Stieg: So where do you go next with this? What’s your goal with the research?

Ori Amir: Well, currently I’m playing around with artificial intelligence. I want to sort of try to mimic to see to what extent you can mimic the process that the human brain does when writing jokes. I don’t think that AI will be as good as humans in generating jokes until it will be as good as humans in pretty much everything else. But being good as humans in pretty much everything else, I believe is around the corner.

Phil Stieg: Well Ori, it’s a pleasure. I truly appreciate you taking the time to explain to us what humor is about, how it’s constructed and where it’s located in our brain. And even though you haven’t found my funny bone, you at least give me kind of map to start thinking about where it is. Thank you for being here.

Ori Amir: Of course. And everybody who listened to it would is now guaranteed to be twice as funny.

Phil Stieg: We can only hope, right? We need more. Trust me. I think we need more humor in the world right now.